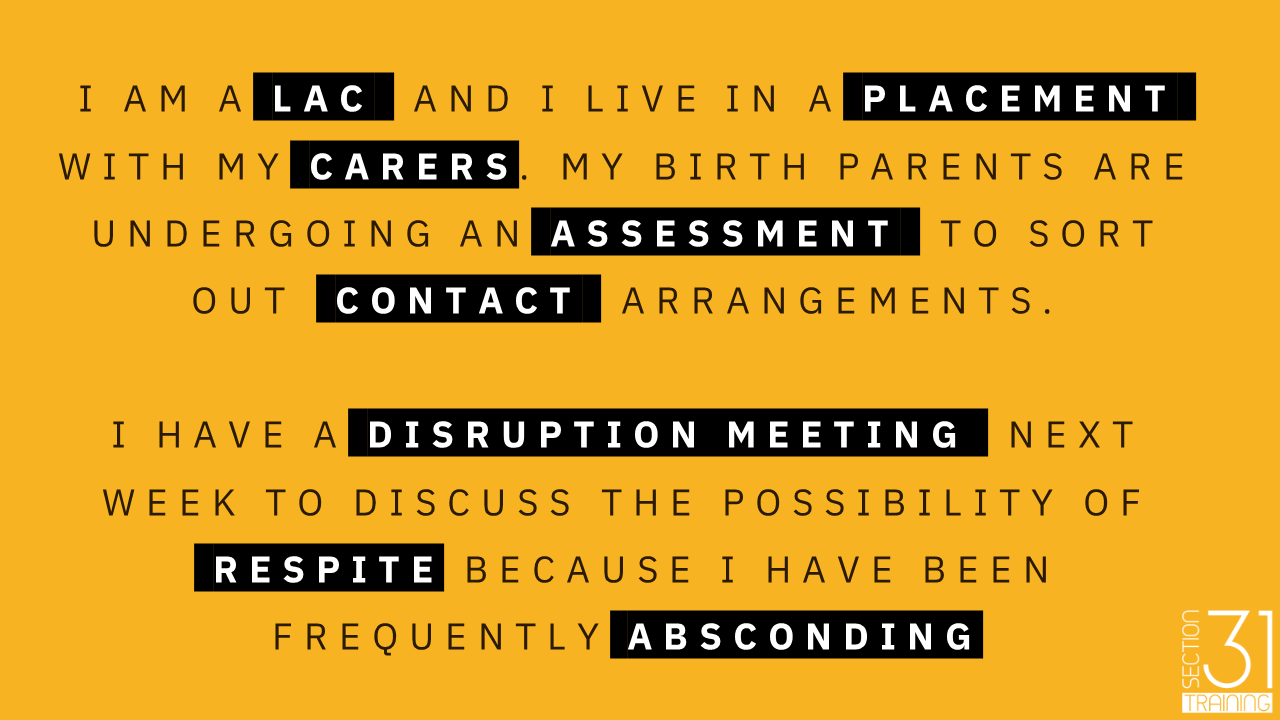

“I am a LAC and I live in a PLACEMENT with my CARERS. My BIRTH PARENTS are undergoing an ASSESSMENT to sort out CONTACT arrangements. I have a DISRUPTION MEETING next week to discuss the possibility of RESPITE because I have been ABSCONDING“.

Is this a normal way of speaking? I think not. But this is the language children in care have to listen to on a daily basis.

Children who grow up in care know they are different, they know their circumstances are not the norm yet a sense of normality is often what they desire more than anything else. Normality represents the light at the end of a long and dark tunnel that children in care find themselves in. The system’s obsession with labelling everything and everyone with clinical dehumanised terms makes normality seemingly impossible to achieve for those who are living within it and it pulls the light at the end of the tunnel further and further away. In the real world we do not label every activity, every action, every thing and everyone, but the care system seems to be absolutely obsessed with doing so.

Married couples do not refer to each other as their “SPOUSE“. When they visit a friend or a family member they do not say “IM HAVING CONTACT“, and when they speak about family matters or try to plan things with their children they don’t call it a “REVIEW” or a “PATHWAY PLAN“. These terms are only used in the care system. Since leaving this care system I rarely, if ever, hear any of these terms being used in the real word. As a care experienced person I can tell you that these words and terms are a reminder that you are a child of the system, a reminder that you and your life is not normal.

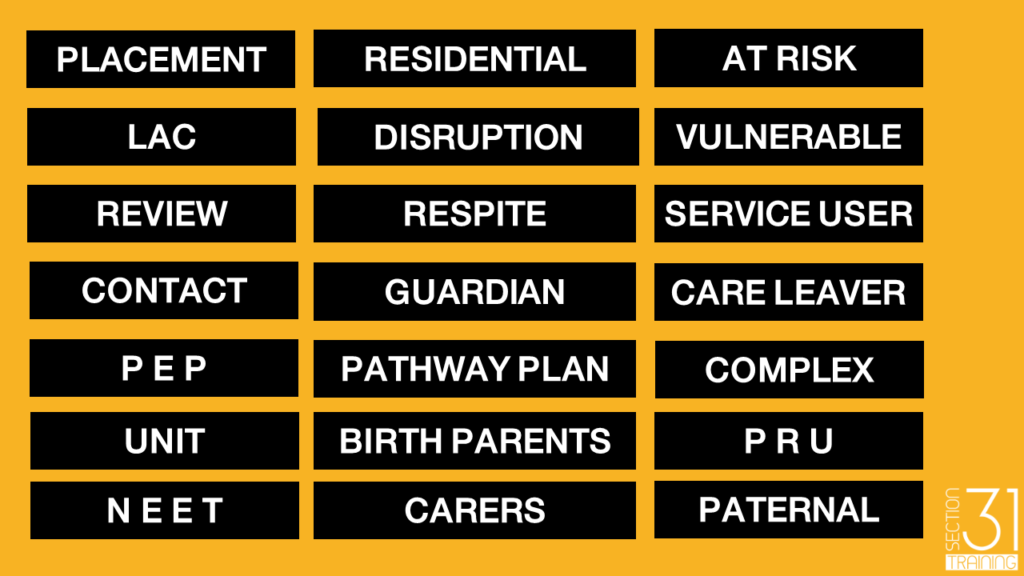

Terms used in the care system to describe children and their arrangements

For those who work in the system these terms may not mean anything more than their dictionary definition. These words allow people to identify and title what something or someone is or does, these words and terms form a language created by that workplace or system to compartmentalise, categorise and identify people, groups, actions and processes. These words and terms are not intended to cause harm. Using umbrella terms, acronyms and blanket statements like this is a way of making things professional, linear, organised and measurable. This isn’t just in the care system though. Every professional workplace, trade or field has its own list of professional terms, often referred to as professional “jargon” but these terms are nearly always exclusively used within that workplace. Outside of the workplace more normalised words and terms tend to be used.

It is hard to completely change the language used within the care system, or any large system because some terms must be used as a point of reference. Often many of these words and terms are imbedded within law and legislation and they are recognised throughout the system and within legal frameworks. The use of these words and terms bring a sense of professionalism to the workplace and everyone working within that field will know what these words and terms mean. If every local authority, agency and organisation within the system used a completely different language it would make communication much worse that it already is. With that being said there is still a lot that can be done to normalise and humanise the system.

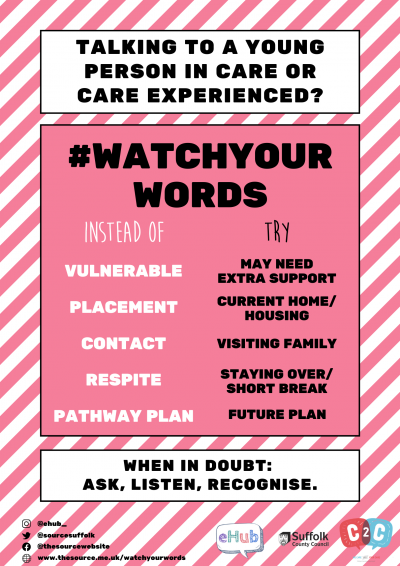

It is becoming increasingly recognised that these terms and words are having a negative impact on children, young people and their families. These words can make people feel ostracized, judged, stigmatised and dehumanised. Many children and young people feel that these terms are used to define who they are and their actual identity is robbed of them in the process. However, more recently, there seems to be a willingness to tackle this issue, in fact many fostering providers are actively looking to change the language they use. A good example of this is Suffolk’s “Watch Your Words” campaign which was recently launched. This campaign gathers thoughts and views from care experienced young people and the campaign clearly demonstrates that a lot of these terms can make young people feel uncomfortable and stigmatised, it is clear that children and young people want these terms and words changed.

the WATCHYOURWORDS campaign encourages professional within the system to use alternative terms

Fostering providers often approach me and ask what I think are better words to be using to replace those currently in use. As is often the case people are desperately trying to find a new one size fits all approach and as always, there isn’t one.

The difficulty you have when trying to change a word or a term within such a vast system is that the new word or term may be better for some but can upset others in the process. The government have exactly the same issue. They bring in a policy that helps one group of people but in the process another group has been disadvantaged by that exact same policy. It is hard to get it right for everyone and a one size fits all approach does not work when you are working with such a large and diverse group of people.

A good example of this is the word ‘Placement’. Young people in the WATCHYOURWORDS campaign have said “current home” or “current housing” are terms they would prefer and, of course, these are much better terms to be using. However for me the word “current” suggests that that home is temporary. For those who are on interim care orders or whom have the possibility of returning to their birth families at some point the term “current home” would of course be appropriate because the foster home and the birth families home are two different things that need to be recognised as such. There are however many children (myself being one of them) who have no chance of returning back to their birth family, who seek permanency and security in long term foster care. Many children in that situation would often prefer to simply use the term “home” and may be more willing to call their foster parents “Mum” and “Dad”.

Personally I wanted foster parents to completely replace my birth parents because I had absolutely zero connection with them whatsoever and they had no interest in seeing me, but there are plenty of children in the system who most certainly do not want foster parents to replace their birth parents. As far as those children are concerned they already have a mum, a dad and a home and this fostering arrangement is just something they are in temporarily.

The point is that every child’s situation is different and the people and places in their lives can represent different things to different children. It is important to be mindful of this when trying to figure out the right wording.

One thing that the WATCHYOURWORDS campaign does highlight is the importance of asking children and young people what words they personally prefer with the campaigns slogan being, “When in doubt: ask, listen, recognise”.

If anything, campaigns like this clearly and quite rightly highlight that the words currently used in the system are outdated, clinical and create stigmas and negative feeling within those who are care experienced, but equally there is no one single alternative term that will please all.

The goal is to try and normalise it all as much as possible and adapt to the individuals you are working with.

There are many terms and words that I didn’t like in care and if I listed them all this blog would soon become a small book. But I want to just focus on a few of these terms, as these I feel had the most negative impact on me as a child living within the system.

Personally this is the one word that bothered me the most in care and still bothers me hearing it now. I remember social workers always asking me “how is your placement going?” . I often hear foster carers or social workers referring to children as “placements”. This term seems to be readily used to define children and / or the homes they live in. I feel that a lot of the time this term is not even used by professionals as it is intended.

Firstly let me just say, children are not placements and they do not live in placements. The “placement” is the arrangement.

I experienced many moves whilst in care, some homes I only lived in for a short while, maybe a week or two but others I stayed in for years. I remember that whenever I was “placed” in a new home initially I just saw that place as a building and the “carers” meant nothing to me really. It was just a building I was put in, there was a room that apparently was mine, there was a dog running around, there was a women over here and a man over there. Nothing meant anything to me in the beginning, there was no attachment. I didn’t like those people but I didn’t dislike them either, they were just some more people that were trying to enter my life.

What foster carers often did was give me a pretty bland room and allow me to customise that room over time. Many took me to IKEA, Dunelm, Asda or some kind of home store and let me pick things for my room. They let me put posters up, choose my bedding, put glow in the dark stars on the ceiling and put things where I wanted them to be. Some even painted my room and let me pick the paint. One let me paint my own room which, of course, resulted in me getting a brand new carpet! Anyway, I eventually made this room my own and it became “my room”.

Many foster homes I lived in had dogs and I loved dogs, especially big dogs. I would always get attached to them very quickly, mainly because dogs seem to just give instant unconditional love and affection but most importantly… they don’t ask questions! A dog would always be the first living soul to enter my very closely guarded inner circle. I would often play with the dog, when I was very young I remember I would tell the dogs stories and I liked to believe they listened to me. In time that dog was no longer just a dog, it was my dog, it was my best friend.

The building I was living in started to become familiar, comfortable and safe and in time it did not feel like just a building anymore, it was my home. Those people that were looking after me in time became Mum and Dad, they were no longer carers to me, they were parents. Although I very rarely addressed any of my foster parents by “Mum” and “Dad”, in my heart I did see them as Mum and Dad and I would refer to them as Mum and Dad when speaking about them to my friends, social workers or anyone outside of my home. To their face, I would instead address them by their first names.

So, in time I learned to know my foster parents as Mum and Dad and I learned to call the house my home. At this point I was beginning to feel somewhat normal, I had normal things with normal labels. Each day that passed was another step closer to the normal life I was so desperately seeking.

Whenever social workers came they would continue to use these professional terms. They would say “how is your placement going “. To me it felt like they didn’t understand that this wasn’t some arrangement for me, it was my home and this was my family.

In their eyes they were on a “visit”, seeing a “looked after child” in their “placement” with their “carers”. It was like they were completely emotionally detached from everything and could not see that I just wanted to live with a Mum and a Dad in a permanent home, in MY home. I just wanted to be normal and so whenever they said “placement” it reminded me that these aren’t my real parents, this is just somewhere I have been put, nothing is real and I am just a “case”. It took away that feeling of normality I had started to feel.

As I mentioned previously, I do not have a relationship with my Mum and Dad, and so I was happy to see foster carers as Mum and Dad, I’ll be honest with you, I wanted to be adopted. I wanted social workers to refer to them as my Mum and Dad and to say “how are things at home” rather than “how is your placement”.

This is just how I feel about it though. The word I wanted to be used was “your home” not “your placement”. However, there are many children that would prefer professionals to not use the words “home” and “Mum” and “Dad” because unlike me, they see their birth families as their parents and their real home is the one they were removed from.

So regardless of a child’s circumstances there is a general consensus that the word “placement” needs to be either binned or at least used properly but the alternative / replacement term needs to be tailored towards each individual child. For me, I would have preferred the word “home”. Children are children though, the term “placement” should not be used to describe them, they are people, not things that have been put somewhere.

Print this out and stick it in your office.

Respite, by definition is a short period of rest or relief from something difficult or negative. This is the dictionary definition and many children see respite as a negative thing because of how this arrangement is presented to them. But it doesn’t need to be negative.

Respite is a normal thing, we just don’t call it that in the real world, that negative connotation is not there. It is normal for parents to ask friends, family or trusted sitters to take care of their children from time to time. This isn’t always because parents have “had enough” of their children. It is quite normal for children to go and stay with grandparents whilst the parents recharge their batteries and it isn’t always because their children have been “naughty”.

For children who have been moved around a lot the term “Respite” can signal feelings of overwhelming anxiety because to them it is a sign that their foster parents may be about to give up on them. Respite should be seen as a break for both foster parents AND children.

In terms of using an alternative word for Respite, we could use terms like “breathing space” or “a break”, but, do we even need to use a word? When children go and stay with their grandparents or their parents trusted friends what would you call that? Respite? A break? Or would you just say something like “you are staying with John and Mary for a week”

In care the “respite” was always something that happened when I was too naughty for too long. There had been times in the past where I was sent on respite whilst my foster parents went on holiday which understandably did not help my feelings towards this arrangement. It always felt like I was being sent away and it always felt like a punishment. The term I thought was more appropriate was “punishment placement” but as I mentioned, respite should not be seen as a bad thing. But there are many children within the system who feel this way about it and the word “respite” carries feelings of anxiety and worry, a sign that the end is near.

I feel that for me, respite would have been better if it was always the same person and that person was someone I spent time with during good times and not just bad times. Sometimes it is not the word itself that is a problem, it is the emotions that a child has learned to associate with that word.

Every time I hear the word “contact” it makes me think of aliens visiting the earth… seriously. This term has always seemed ridiculous to me. My brother and I are now adults and sometimes when we see each other now we say “are we having contact” and we have a little laugh about it, we make fun of how ridiculous the term is and how normal we was led to believe it was to use that term as children. I remember once at primary school a friend asked me what I was doing after school and I said “I’ve got contact with my brother”. My friend looked at me all confused and simply said …”what?” I went on to explain and he said “oh, your seeing your brother?”. My friend was bewildered by the word “contact” but I had learned that to be a normal thing to say.

Whenever a child in care spends any time with any significant person outside of the foster home it is considered “contact”. We would never use this term in the real world… ever.

The term “contact” is in my view the worst offender when it comes to using clinical, dehumanised terms. How hard is to just say “visiting friends or family” or just “spending time with”?

The term “contact” if anything insinuates an aspect of control over a relatively normal thing.

The look my friend gave me when I told him “I’m having contact”

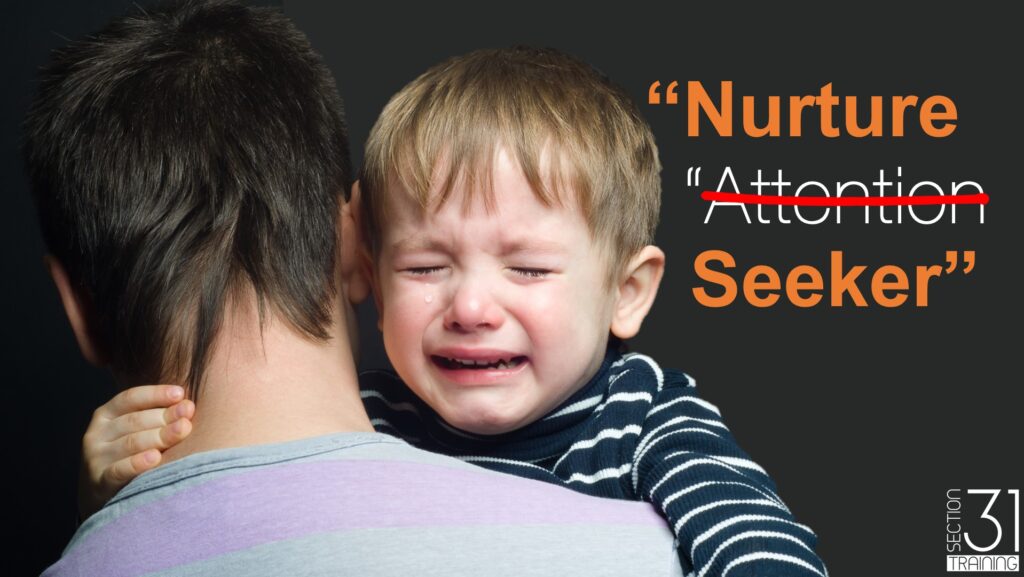

What affected me most in care, aside from all the weird and wacky terms that were used to describe me and my life was blanket statements and generic behavioural labels. I was considered to be quite a “challenging child”, I was a “naughty kid”. The system and everyone around me seemed obsessed with finding fault, and trying to fix my problems. There was also a huge focus on my surface behaviours.

I was assessed and analysed by everyone who entered my life. My referrals are littered with terms such as “aggressive”, “attention seeker” and “manipulative”. Hearing these terms absolutely hammered my self-esteem and made me believe that these words are what I really am. These labels were assigned to me and treated as truth by anyone who entered my life.

The system taught me that I am a bad kid with a bucket load of problems and it made it very hard for me to see the many skills and strengths that I have since realised I have. Everything you do in care is looked at through a microscope. I remember when I was 14 at secondary school I used to draw willies on the wall and would occasionally shout out sexual words but… so did my friends. We were just boys in puberty yet it was only me who was labelled “sexualised”.

I was labelled as a “Firestarter” because I accidently lit one thing on fire.. once. Meanwhile my best friend is setting off bangers and fireworks in his garden but was he considered a “Firestarter”, nope… just me… because I am in care.

If I didn’t come back to “my placement” on time people would say I have “absconded” or they would say I am “missing”. No, I am just out with my friends.

Blanket statements and behavioural labels are useless unless they carry context. Many children are labelled generically over something they did once or over something they do which is misunderstood by those around them. Above all else they are children, they are human beings and who they are should not be defined by the mistakes they have made along their difficult journey.

Understanding is key. Change the word, change the response

So in conclusion, the words and terms used within the system need to be changed.

Ultimately when it comes to finding the right words to use, know your children, know their situation, listen to them. What words are they using to describe things when they speak? Let them decide what they want to call things and refer to those things in the way in which that individual child has chosen to. Every child in care is in care for different reasons, they are all on their own unique journey and they will all have different feelings towards their situation and the people around them. Stop looking for a script. Rather than trying to find perfect labels it is best to try and eradicate labels altogether when talking to children, young people and their families. For children in care, their life is complicated enough without using all this unnecessary clinical jargon.

There are times where these words and terms may need to be used such as in court or during a professional meeting but see that as your “phone voice”. When it comes to actually engaging with children and their families take off your phone voice and use normal words, you will be seen as no less of a professional for doing so, you will be seen as a human who makes sense and those you speak to will feel “normal”.

Normal is all these children want to be.

To end, I will share a video I made with a group of young people to really drive home just how damaging behavioural blanket statements can be and how context can change everything.

Thank-you for taking the time to write this. I couldn’t agree more! I was fostered at an early age and then adopted, I am now a social worker and a foster carer in Australia.

I agree we need to take a look at what labels we use, we also need to listen to our children in care, our carers and our parents who have had their children removed, we need to ensure we are seeing them for who they are and really listening to how they see their situation.

Unfortunately the system/caseworkers do not see children or carers, and I would say the parents who have lost there children as actual people, they see them as you mentioned above, as a case. This does not help kids in care feel settled and carers feel certainty. I cannot talk for how the biological parents feel

Blogs like this, or training, should be widely shared amongst these services to help them understand and in turn work with more understanding and less clinically.

I love what guys are all about, great idea!

That was very insightful and helped me put myself in the child’s shoes and even gave me some important clues as to where we as foster carers and children want to be in relation to each other. We all desire a sense of normality and that sense is only formed around the child in the circumstances, which are not their choice. Any child is a normal and unique at the same time. Being born and being alive is a great opportunity and we help the child realise their potential but above all develop their personality and identity, which will make them confident and content. That’s the main life skill.